Summary

Prepared by Julia Ash, a sophomore Baylor University Scholars major, this exhibit examines the often unjust relationship between Ukraine and the Soviet Union, and gives some context to the current war in Ukraine against Russia.

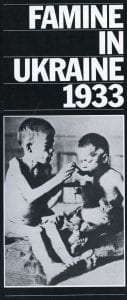

Holodomor

Holodomor, also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was an artificial famine that surged in the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic (Ukrainian SSR) in 1932 and 1933. Holodomor was a part of the broader Soviet famine of 1932-1934 which affected the prominent grain-producing areas of the country. The Ukrainian famine was deadlier due to a series of political decrees and decisions that were aimed mostly or only at Ukraine. The famine of 1932–33 is often referred to as Holodomor, a term derived from Ukrainian words for hunger (holod) and extermination (mor).

The most affected regions of Holodomor included Kharkiv Oblast, Kyiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Odesa, Vinnytsia, and Donetsk oblasts.

In Action

Holodomor began with teams of Communist Party agitators forcing peasants to relinquish their land, personal property, and housing to collective farms. The agitators deported kulaks, or wealthier peasants, as well as any peasants who resisted collectivization. Collectivization led to a significant drop in production, disorder in the rural economy, and tremendous food shortages. Extremely unpopular with the peasants, and some areas revolted. The rebellions worried Stalin because they were happening in provinces that had fought against the Red Army during the Russian Civil War. In the autumn of 1932, the Soviet Politburo – the elite leadership of the Soviet Communist Party – decided to widen and deepen the famine in the Ukrainian countryside to again assert its power. Farms, villages, and whole towns in Ukraine were placed on blacklists and were prevented from receiving food. Peasants were forbidden to leave the Ukrainian republic in search of food. Despite the growing starvation, food requisitions were increased, and very little aid was provided. The crisis reached its peak in the winter of 1932–33 when organized groups of police ransacked the homes of peasants and took everything edible, from crops to personal food supplies to pets.

Grave Results

In the spring of 1933, death rates in Ukraine spiked. At least 7 million people died of hunger between 1931-1934. Among them were at least 4 million Ukrainians. Soviet police archives contain multiple descriptions of instances of cannibalism, lawlessness, theft, and lynching. Mass graves were dug across the countryside for the bodies that multiplied.

A bigger Assault on Ukraine

The famine was followed by a larger assault on Ukrainian identity. While peasants were dying by the millions, agents of the Soviet secret police continued to target the Ukrainian political establishments and intelligentsia. The famine provided cover for repression and persecution against Ukrainian culture and Ukrainian religious leaders that continued until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

KGB Arrests

How and Why?

In 1972 and 1973, the Russian KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti – Committee for State Security) arbitrarily arrested several thousand Ukrainian intellectuals, students, and workers in Soviet Ukraine. A large wave of arrests began in January 1972 on directives from the Central Committee of the Communist Party in the USSR. The purpose of the purge was to eliminate all forms of opposition in Ukraine to the policies of russification. For many years, the Communist Party tried to squash the aspirations of Ukrainians to retrieve their national identity and save themselves from being assimilated into a “united Soviet nation” which was really the Russian nation.

Who?

In 1973, Russian authorities conducted a widespread purge of party and government organizations in Ukraine. Many officials, despite their communist upbringing in “Soviet Society,” were considered Ukrainians. They were dismissed from office and replaced by Russians or so-called Ukrainians who proved subservient to Moscow’s rule. The purge also swept most of the editorial boards in Ukrainian publications. The same process was employed throughout the educational structure from universities and colleges, through secondary and primary schools, down to kindergarteners. Hundreds of Ukrainian writers, professors, lecturers, teachers, students, and factory workers were persecuted, interrogated, and harassed by the KGB to keep silent about what was really happening in the Ukrainian nation.

Stalin’s Terror Recalled

The wave of arrests and persecution recalled Stalin’s terror in Ukraine between 1929 and 1933 when more than 7 million Ukrainian peasants perished as a result of an artificial famine and more than 52,000 Ukrainian intellectuals and workers were liquidated in prisons or concentration camps. During similar purges between 1936 and 1938, in the province of Vinnytsia alone, more than 10,000 people were shot without trial, and a public park created on top of their graves.

Among the many victims of Russian brutality were historian Valentyn Moroz, Yuriy Shukhevych, publicist Sviatoslav Karavansky, Ivan and Nadia Svitlychny, Ihor and Irena Kalynets, Leonid Pushch, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Mykhaylo Osadchy, Vasyl Stus, Vyacheslav Chornovil, Ivan Hel’, Lev Lukianenko, Ivan Kandyba, Rev. Father Vasyl Romaniuk, Taras Melnychuk, Irene Senyk, and Kuzma Dasiv.

First Ukrainian Woman Sentenced in the USSR During International Women’s Year

Article 17 of the Soviet Constitution of 1936 stated that every union republic had the right to secede from the Soviet Union, implying that citizens of any republic had the right to advocate such a secession. But these rights were never officially recognized as absolute, nor did the Soviet Union ever make a distinction between political and common law crime since the structure of Soviet society, theoretically, precluded one. Oksana Popovych, however, saw a distinction between the two, and though completely disabled and dependent on crutches, she continued to work toward her goal of self-determination for Ukrainians. Oksana Popovych was only 16 when she and her school friend were arrested for working in the movement for Ukrainian self-determination. Her friend was shot, but Popovych served a 10-year prison term which severely damaged her physically due to hard labor.

Returning to Ukraine in 1955, Oksana Popovych was denied a resident’s permit for her home province of Ivano-Frankivsk and made to live in a mud hut with her aged mother, the widow of well-known Ukrainian writer Les Matrovych. She managed to finish her secondary education and took a two-year course in German but was denied admission to the university. Instead, she became an excellent historian. Unfortunately, her physical condition continued to deteriorate, and she was admitted to the hospital for an operation that proved unsuccessful. While awaiting further surgery, she was arrested again in November of 1974 and put on trial. She pleaded not guilty to “anti-Soviet agitation(anything construed as being carried on for the purpose of subverting or weakening the Soviet regime or the circulation of “slanderous fabrications” which defame the Soviet state and social system) and propaganda” and distribution of samizdat (underground newspaper). At the conclusion of her trial, Miss Popovych, aged 47, still awaiting her operation, was sentenced to eight years’ exile. The sentence included transportation to an area under strict supervision by local state and police authorities. Her blind mother was left to fend for herself. Miss Popovych, whose last job was in a power station, served her sentence at Mordovia, 280 miles south of Moscow. According to reporters, the prisoners worked sewing mittens. They were expected to meet high quotas despite inadequate lighting and scarce food supplies which left them malnourished and with no strength.

Miss Popovych’s imprisonment took place at the same time that Ukraine and the USSR, as well as the other countries, were preparing for the observance of the International Women’s Year declared by the United Nations.

Post-Soviet Ukraine

Ukrainian Rebirth after 1991

After the fall of the Soviet Union in December 1991, Ukraine held a referendum to determine whether Ukraine should begin its journey as an independent state. About 84% of the eligible population voted, and around 90 % of them endorsed independence, securing Ukraine’s rebirth as a free nation.

Coinciding with the referendum, Ukraine held its first presidential election, and Leonid Kravchuk was chosen. By the time the referendum was held, the Communist Party and its development was disbanded, and Konstiantyn Morozov was elected as the first Minister of Defense.

At the same time, Ukraine also resisted constant pressure from Moscow to forfeit its independence and reconsider entering a reconstructed version of the Soviet Union.

A week after the referendum for independence, the leaders of Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus held another referendum and agreed upon establishing the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), a free association of sovereign states to replace the crumbling Soviet Union. The three initial Slavic republics were subsequently joined by the Central Asian republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, and by the Transcaucasian republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Moldova. The CIS formally came into being on December 21, 1991, and began operations in January 1992 with the city of Minsk in Belarus as the administrative center. The CIS coordinated members’ economic policies, environmental protection laws, and other law enforcement.

Ukraine officially declared its independence on August 24, 1991.

Following the Independence

Aspiring to be integrated into the European Union, Ukraine put forth transformational efforts, but by the end of the 20th century, the economy in the country faltered, and social and political changes in Ukraine fell short of transforming Ukraine into a prosperous EU candidate. Despite the failed attempt, Ukraine continued to make progress. First, the country consolidated its hard-won independence, developed its state structure, regularized, and widened relations with its neighbors, progressed in the process of democratization, and established itself as a strong and reliable partner in international relations and trade.

Ukraine Today

In the early morning of February 24, 2022, Ukraine faced a full-scale invasion by Russian forces with the goal of completely destroying and replacing the democratic government system of Ukraine. Today, the Ukrainian government and Ukrainian people remain resolute in their efforts to preserve and retain independence, being governed solely by the people of Ukraine.

Religion in Ukraine

When Kyiv was the capital of ancient Russia, Prince Vladimir adopted the Christian faith and decreed that his people should be baptized as he was. The main street in Kyiv was named “Kreschatik” from the Russian word “baptism” and the event marked the beginning of the Eastern Orthodox Church which came to Kyivan Rus at that time. The Eastern Orthodox transitioned into the Russian Orthodox Church and grew into a powerful force, the undisputed “ruling Church” until 1917. The capital of Kyivan Rus was later moved to Moscow, but Ukrainians continued to remember their past glory. Many Ukrainian nationalists resented the Soviet policies in Ukraine. That nationalist feeling manifested itself in uncensored writing and occasional outbursts of violence which were suppressed.

Communism against the Cross

All denominations in the Soviet Union suffered from the atrocities of the state’s atheist rule. Part of the Soviet plan was to promote the Russian Orthodox Church and specifically to downplay and eventually abolish the Ukrainian Church. Because the Ukrainian Church belonged to the “intelligentsia” category in the Soviet Union and was a source for free information, personal choice, and a different body of authority the main goal of the KGB was to destroy the church through persecution, interrogation, and propaganda. In the early and mid-1980s, anti-Christian propaganda was increased, atheism was taught in schools, criminal charges were made against Christians in villages, and a special “psychiatric department” was sectioned off for those who were arrested for religious affiliation. Hundreds of Ukrainian believers were subjected to harsh treatment and carried their crosses until their last breaths knowing that they were laying a path for future freedom.

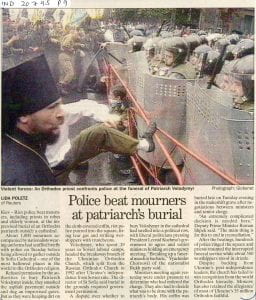

Ukrainian Church Today

Today, Ukraine is home to well-known Christian denominations including Orthodox, Greco Roman Catholicism, Roman Catholicism, Protestant, Evangelical, and non-denominational groups which flourish. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church was revived after 1991 along with the societal view of the Church. During the 2014 Maidan Revolution when peaceful Ukrainian protests were put down with brute force sent by Russian oligarchs, many believers made themselves known by setting up prayer tents, attending to the wounded, delivering food, and shining the light on those who needed it the most. During the current war, church gatherings moved online or to basements and apartment buildings that still stood. Many believers continue to carry their crosses, knowing they are laying the path to future freedom.