INTRODUCTION

Although the Keston Center for Religion, Politics, and Society is best known for its collection of anti-religious materials, religious underground publications, and library, its holdings also contain Soviet-era propaganda posters that comment on a variety of Cold War era events and themes. Undergraduate students in HIS 4379: The Cold War, taught by Dr. Julie deGraffenried and Dr. Stephen Sloan, selected a poster in the Keston collection to analyze, chose an element from the poster to investigate, and wrote up their findings in a brief essay. Students engaged in two rounds of peer review and made oral presentations of their work to their classmates before submitting the final product. Here we present the work of those students adjudged most successful.

Claire Keck | Cool Means Competence: Color Theory in Soviet Art

Anti-religious poster form 1984 comparing an athlete to an old woman carrying bottles marked “holy water” and “from the evil eye.” View the poster’s full digital collection item at https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/anti-religious-poster/1064065.

The Soviet Union was not widely regarded as a champion of religious liberty. Throughout the Cold War, the Soviets were regarded as predominantly atheist and the antithesis of Western Christianity. This anti-religious poster, published in June 1984, demonstrates Soviet support of atheism. The poster depicts two women: one, a strong and successful non-religious woman, and the other downtrodden, religious, and unsuccessful. While the two characters in the poster are certainly interesting, even more striking is the juxtaposition of color. The successful woman is clothed in blue, and she holds a golden trophy. Her hair, like the trophy, is golden. The unsuccessful woman is clothed in drab colors, and the only color in this poster are the blue bottles. In this poster, propaganda artists used color as the primary means of communicating their message.

The use of color was one of the most important aspects of creating propaganda posters. Studies of peasant focus groups in the 1930s Soviet Union revealed a preference for muted colors and the color blue, as opposed to colors that had been more common in Tsarist Russia, like stark blacks and reds. [1] This echoes elements of color theory. The color blue is associated with competence, as it is perceived to reflect intelligence, communication, trust, efficiency, duty, and logic. [2] The successful woman is dressed in all blue, reflecting her competence, intelligence, trustworthiness, efficiency, and fulfillment of her Soviet duty. The religious woman is dressed in dark colors, harkening back to the distaste of the peasant focus groups. The religious woman is supposedly incompetent, unintelligent, untrustworthy, inefficient, and failing her duty to the Soviet Union. The successful woman has golden hair and holds a golden trophy. Like the color blue, this emphasizes the use of color theory. Yellow tends to allude to a “cheerful facet of sincerity” because it generally evokes feelings of optimism, extraversion, friendliness, happiness, and cheerfulness. [3] The successful woman is optimistic, cheerful, friendly, and happy, while the religious woman on the other side of the poster is sad, despondent, and weary.

The use of women in propaganda posters was originally uncommon in the Soviet Union. In the earliest years of the Soviet Union—particularly after the revolution and the civil war—women were not seen as frequently in propaganda as they were by the Stalinist era. As propaganda began to glorify young, vibrant women as willing participants in forced collectivization in the early 1930s, the belief was that the picture of an ideal woman might encourage women into behaving in an acceptable and predetermined way. [4] The successful woman is depicted as young and vibrant; the religious woman is depicted as old and muted.

The purpose of propaganda is to spread particular ideologies among the masses. Propaganda artists who created propaganda art in the USSR recognized that even in a society that was built around a commitment to a particular ideology, applying those principles in everyday life brought its own challenges. [5] To combat this in the anti-religious poster, the two women depict a familiar picture: one of success and one of poverty. Furthermore, the use of blue, yellow, and grey help accentuate this picture. Propaganda workers had to do more than simply repeat doctrines; they had to create a graphic design that embraced color choices, calligraphic style, and illustration. [6] The purpose of propaganda art in the Soviet Union was to marry the joy of creativity with the political goal to shape a populace that was gladly participating in socialist construction. [7] Soviet propaganda owed its success to its cooperative use of color schemes, illustrative styles, formats, and iconography that was familiar to the general public throughout the early years of the Soviet Union. [8] Even by 1984, these methods influenced the style of Soviet propaganda art.

[1] Scott Boylston, “Visual Propaganda in Soviet Russia,” Academia.edu, April 18, 2022, https://www.academia.edu/6387163/A_Study_of_Soviet_Propaganda. [2] Lauren Labrecque and George Milne, “Exciting red and competent blue: the importance of color in marketing,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40 (2012): 714. [3] Labrecque and Milne, “Exciting red,” 714. [4] Boylston, “Visual Propaganda.” [5] Sonja Luehrmann, “The Modernity of Manual Reproduction: Soviet Propaganda and the Creative Life of Ideology,” Cultural Anthropology 26 (2011): 364-365. [6] Luehrmann, “The Modernity of Manual Reproduction,” 368. [7] Luehrmann, “The Modernity of Manual Reproduction,” 368. [8] Boylston, “Visual Propaganda.”

Hattie Krawiecki | The Olympic Role of Detente

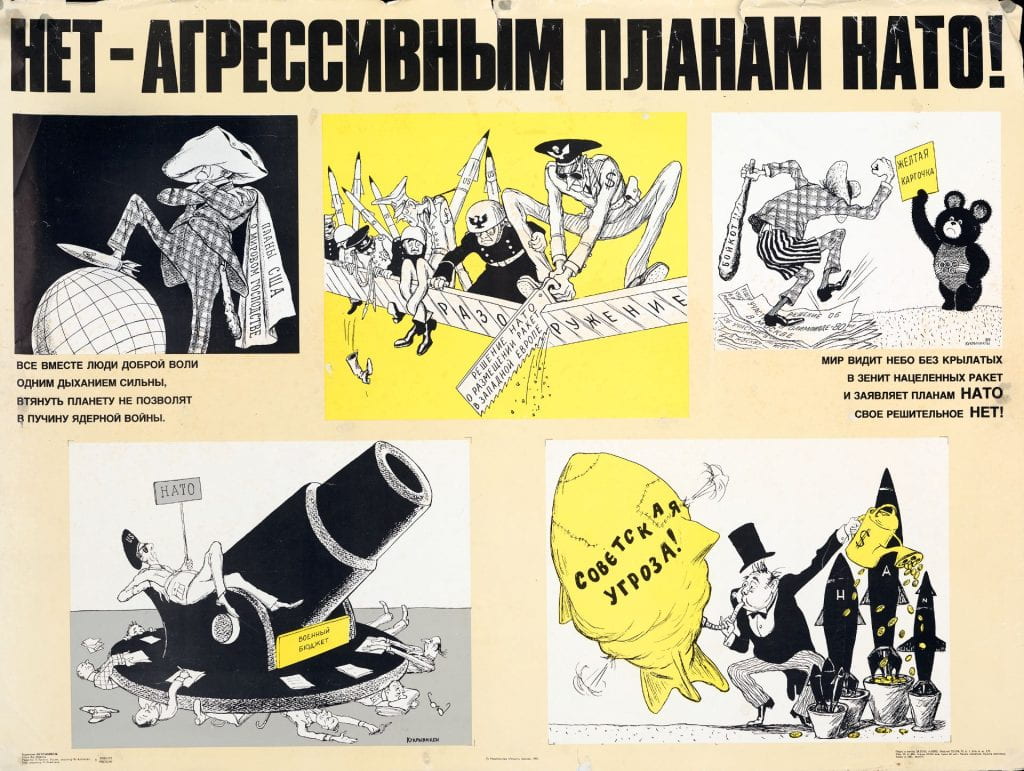

Soviet anti-NATO (“No to agressive plans of NATO!”) from 1980. View the poster’s full digital collections item at https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/net-agressivnym-planam-nato/1064179

Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan on December 24, 1979, U.S. President Jimmy Carter called for a boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics to be held in Moscow. This decision was met with both critics and supporters alike. In his address to the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) on April 12, 1980, U.S. Vice President Walter Mondale stated, “history holds its breath; for what is at stake is no less than the future security of the civilized world.” [1] The USOC decided to uphold the call for a boycott of the Moscow Olympics despite opposition from athletes. The Soviet press deemed the “Washington administration” responsible for pressuring and blackmailing the committee into the boycott. [2]

This late Soviet era poster “Net agressivnym planam NATO” (No to the aggressive plans of NATO) contains five scenes criticizing the actions of NATO. In the upper right-hand corner, the Soviet Olympic mascot, a bear cub named Misha is seen holding a “yellow card” towards a man angrily stomping his foot and holding a wooden club with the Russian word for “boycott.” [3] At first glance the man appears to be Uncle Sam because of his pinstripe shorts, but he could also be interpreted as a person from small town USA stereotyped as a country bumpkin. The translated text at the bottom of the poster declares “the world sees a sky without winged things and cruise missiles and declares to NATO’s plan a resounding no!” NATO met in Dec 1979 and planned to install the “new American nuclear missiles” in Western Europe. [4] This decision coincided with the timing of the U.S. led boycott of the Olympics; the poster simultaneously condemns both actions because the U.S. was seen by the Soviets as the Western leader of NATO.

When President Carter announced the U.S. was not sending a delegation of athletes to the 1980 games, many nations were faced with a dilemma: to join the U.S. boycott or to send their delegation to Moscow. Effectively, this caused nations to pick sides. When the Soviet Olympic Organizing Committee was formed in 1975, they estimated 130 to 140 countries, 12,000 athletes and coaches, and over 7,000 representatives of the press, radio and television would attend the Moscow Olympics. [5] In actuality only 80 nations attended, only 5,179 athletes participated, and the U.S. cancelled all televised coverage of the games. [6] Surprisingly, nations such as Great Britain and Australia did not join the boycott despite their ties to the United States. [7] Despite what officials in the Soviet Olympic Committee and International Olympic Committee called “highhandedness” no penalties were imposed on the U.S by the International Olympic Committee (IOC). [8] The portrayal of an unsmiling Misha the bear holding a yellow card shows the animosity of the Soviets towards the U.S. led boycott. The Soviets responded to the boycott by refusing to send their own athletes to the 1984 Olympics held in Los Angeles, and ultimately both boycotts were signs of the end of the period of détente between the two Cold War superpowers.

[1] “Address by Vice President Mondale to the United States Olympic Committee, ‘US Call for an Olympic Boycott’,” History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, April 12, 1980. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/123796 [2] S. Bliznyuk and V. Geskin, “The World Prepares for the Moscow Games: The Doors Are Open to Everyone. At the 1980 Olympics Organizing Committee’s Press Conference,” The Current Digest of the Russian Press 32, no. 15 (May 1980): 6, https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/doc/13625863. [3] “Mascot of Olmpiad-80,”The Current Digest of the Russian Press 51, no. 29 (1978): 23. https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/doc/13634020. [4] M. Kostikov, “International Notes: NATO Sets Out Snares,” The Current Digest of the Russian Press 32, no. 32 (September 1980): 13, https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/doc/13626950. [5] “The 1980 Olympics: Problems and Prospects,” The Current Digest of the Russian Press 27, no. 35 (September 1975): 19, https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/doc/13638316. [6] “Moscow 1980,” Olympic Games, accessed April 11, 2022, https://olympics.com/en/olympic-games/moscow-1980. [7] Allen Guttmann, “The Cold War and the Olympics,” International Journal 43, no. 4 (1988): 561, https://doi.org/10.2307/40202563. [8] S. Bliznyuk and V. Geskin, “The World Prepares for the Moscow Games: The Doors Are Open to Everyone. At the 1980 Olympics Organizing Committee’s Press Conference.”

Bibliography

“Address by Vice President Mondale to the United States Olympic Committee, ‘US Call for an Olympic Boycott’.” History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive. April 12, 1980. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/123796

Bliznyuk, S. and Geskin, V. “The World Prepares for the Moscow Games: The Doors Are Open to Everyone. At the 1980 Olympics Organizing Committee’s Press Conference.” The Current Digest of the Russian Press 32, no. 15 (May 1980): 6-23. https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/doc/13625863.

Corthorn, Paul. “The Cold War and British Debates over the Boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics.” Cold War History 13, no. 1 (October 2012): 43–66. doi:10.1080/14682745.2012.727799.

Guttmann, Allen. “The Cold War and the Olympics.” International Journal 43, no. 4 (1988): 554–568. https://doi.org/10.2307/40202563.

Kostikov, M. “International Notes: NATO Sets Out Snares.” The Current Digest of the Russian Press 32, no.32 (September 1980): 13-14 https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/doc/13626950.

Olympic Games. “Moscow 1980.” Accessed April 11, 2022. https://olympics.com/en/olympic-games/moscow-1980.

“Mascot of Olympiad-80.” The Current Digest of the Russian Press 29, no. 51 (January 1978): 23-23. https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/doc/13634020.

“The 1980 Olympics: Problems and Prospects.” The Current Digest of the Russian Press 27, no. 35 (September 1975): 19-20. https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/doc/13638316.

BENJAMIN MURPHY | Strong Side, Blind Side

Soviet poster (“The forces of peace are invincible!”) from 1950. View the full digital collections item at https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/sily-mira-nepobedimy/1064181

The Soviet victory of World War II validated the system by which the Soviets lived. The sacrifices made by the people of the Soviet Union were seen as a strength of their system. The Soviet Union promoted international peace based on this perceived position of strength. The Soviets viewed the West as warmongering, or hostile to communism, with the idea deriving from Marxist teachings claiming war would be inevitable. The Soviets aimed for unification of the world’s socialist people who advocated for peace in order to dismantle the economic system that ultimately caused the war.

This poster, created by the famed graphic artist Boris Efimov in 1950, illustrates the call for peace and promotes the idea of Western warmongering. [1] Depicted is a scale, with one arm representing Soviets with the inscription “for lasting peace” and other representing the West bears the inscription “for the new war.” In the context of this poster’s creation, Stalin and his leaders believed in the inevitability of war with the West, but also in the inevitability of Soviet victory.

Military alliances and the military buildup by the West further legitimized the Soviet concern of war. The formation of NATO in 1949 and arming of European states by the U.S created a war hysteria in the country and supported the Soviet claims. [2] President Eisenhower authorized storage of nuclear weapons at NATO bases in Europe to combat the Soviet Union if needed. [3] The arming of Western European countries was perceived as an act of aggression and an attempt to prepare for a new war with the Soviet Union. Anti-Soviet propaganda in western countries groomed their populations. [4] These campaigns were viewed as promoting a war to crush their economic rivals and eliminate any other systems seen as an ideological challenge.

Ultimately, the West was not the only group guilty of employing propaganda, as directly illustrated by this poster. The strength of the Soviet position is depicted in this piece via the giant fist tipping the scale, implying greater relative might. This further suggests fighting for lasting peace with support of the world’s workers is stronger than the Western cycle of war. [5] Soviet efforts to promote international peace reached communist groups on an international scale, such as the French Communist Party, where more than one million people gathered to speak out against militant alliances. [6] Uniting these groups was seen as a strength Western nations lacked. The Soviets instigated these demonstrations to display they were the world’s force of peace against the Western countries.

[1] Boris Efimov, “Sily mira nepobedimy!”, (Moscow, 1950). [2] M. Marinin, “International Review: A NEW STAGE IN THE ‘COLD WAR’ OF THE AMERICAN IMPERIALISTS,” The Current Digest of the Russian Press, 1, no. 33 (September 1949): 28. [3] Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. armscontrolcenter. August 18, 2021. https://armscontrolcenter.org/fact-sheet-u-s-nuclear-weapons-in-europe/ (accessed May 2022). [4] “FOR A LASTING PEACE, AGAINST INSTIGATORS OF A NEW WAR.-Celebrations in Honor of Humanity in Paris,” The Current Digest of the Russian Press, 1, no. 37 (October 1949): 28. [5] “IN DEFENSE (Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation 2021)OF PEACE, AGAINST THE INSTIGATORS OF A NEW WAR!-Formation of a Preparatory Committee for Calling a Nation-Wide Conference of Supporters of Peace,” The Current Digest of the Russian Press, 1, no. 28 (August 1949): 47. [6] FOR A LASTING PEACE, AGAINST INSTIGATORS OF A NEW WAR.-Celebrations in Honor of Humanity in Paris 1949, The Current Digest of the Russian Press, 1, no. 37 (October 1949: 28.

Bibliography

Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. armscontrolcenter. August 18, 2021. https://armscontrolcenter.org/fact-sheet-u-s-nuclear-weapons-in-europe/ (accessed May 2022).

Dolgorukov, Boris Ephimov. “Sily mira nepobedimy!” Keston Center – Keston Digital Archive. State Publishing House “Isskustvo”. Moscow, 1950.

“FOR A LASTING PEACE, AGAINST INSTIGATORS OF A NEW WAR.-Celebrations in Honor of Humanity in Paris.” Current Digest of the Russian Press, The 1, no. 37 (October 1949): 28.

“IN DEFENSE OF PEACE, AGAINST THE INSTIGATORS OF A NEW WAR!-Formation of a Preparatory Committee for Calling a Nation-Wide Conference of Supporters of Peace.” Current Digest of the Russian Press, The 1, no. 28 (August 1949): 47.

“LATEST EDITION OF ‘FOR LASTING PEACE, FOR PEOPLE’S DEMOCRACY!’.” Current Digest of the Russian Press, The 1, no. 9 (March 1949): 32.

Marinin, M. “International Review: A NEW STAGE IN THE ‘COLD WAR’ OF THE AMERICAN IMPERIALISTS.” Current Digest of the Russian Press, The 1, no. 33 (September 1949): 28.

Elizabeth Anne Palmer | They Just Don’t Understand

Soviet propaganda poster from 1979. View the full digital collections item at https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/soviet-poster/1064081

This poster, created by Efimovsky in 1979, illustrates the Soviet Union’s view that Western media has misunderstood the intentions of Soviet law enforcement. As a Soviet policeman is arresting a man wearing a cross, another man, from the United States, is taking a picture of the arrest with the camera aimed at the cross. The description on the poster emphasizes that even though the man was arrested for a violent felony, as seen by the ambulance at the scene of the crime, Western media would wrongfully portray the arrest as a form of religious persecution. In the poster, the American photographing the crime conveniently omits the swarm of nurses and an ambulance in his photos of the arrest.

During the 1970s, there was a great deal of Western interest in cases of alleged religious persecution and of the violation of human rights in the Soviet Union. In 1975, the Helsinki Accords were published, which guaranteed basic human rights for all citizens of the countries that signed them. In the late 1970s, many Helsinki Watch Groups began to emerge in the Soviet Union, composed of people watching to make sure Soviet authorities lived by the Accords they signed, especially in the way of religious freedom. [1] These watch groups oftentimes reported abuses of human rights through appeals to Western media and leaders. Many times, the West openly supported Helsinki groups and stood by them throughout repression. For example, the United States supported Helsinki groups when they were defending themselves against Soviet slander, though this support did not necessarily end repression or stop arrests. [2] The idea portrayed in Soviet propaganda like Efimovsky’s poster was that the West would frame lawbreakers as persecuted individuals in need of help – a misunderstanding according to Soviet authorities, but according to evidence, not necessarily as unrealistic as the Soviets portrayed it.

An example of watch groups funneling information to the West was presented at the 50th meeting of the Third Committee at the United Nations on November 23, 1980. Senator Robert W. Kasten of the United States read a letter from a Soviet woman expressing evidence of Soviet religious persecution. [3] One of the most compelling examples of persecution in this letter was the arrest of Zoya Krakhmalnikova, an editor of samizdat Christian writing in the Soviet Union. She was arrested without warning for writing on “purely religious” subjects. [4] This appeal to the West was one way in which the watch groups and other dissidents made their plight known outside their borders. Western media’s portrayal of religious persecution in the Soviet Union was also expressed in newspaper articles. In a 1985 article in The Times (London), there were three examples of men losing their jobs, getting arrested and having their lives upturned because they were Jews. The author of the article, Bernard Levin, writes about Jewish men wishing to emigrate to practice their faith and Soviet officials denying them exit visas or arresting them for a fabricated cause. [5] Throughout the article, Levin presents many examples of this repression, and concludes by expressing that these cases led him to believe that Soviet leadership wished to “crush out of existence the very notion of a Jewish culture and identity.” [6]

In this poster, the USSR alleges a misunderstanding on the part of the United States about the arrest of this lawbreaker. In reality, there was a great deal of evidence supporting the United States’ concerns about religious persecution and human rights violations in the Soviet Union, as seen in the letter read at the United Nations and the article about religious persecution written in the West.

[1] Lyudmila Alexeyeva, Soviet Dissent (Wesleyan University Press, 1984), 339-340. [2] Alexeyeva, Soviet Dissent, 342-343. [3] United Nations, Third Committee. Summary record of the 50th meeting. New York, NY: UN Headquarters, 23 November 1982. [4] United Nations, Third Committee. Summary record of the 50th meeting. New York, NY: UN Headquarters, 23 November 1982. [5] Bernard Levin, “Where living the faith is now a crime; Persecution of Jews in the Soviet Union,” Times (London, England), 4 Nov. 1985. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A117948107/AONE?u=txshracd2488&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=af9dd3fa. [6] Bernard Levin, “Where living the faith is now a crime; Persecution of Jews in the Soviet Union,” Times (London, England), 4 Nov. 1985. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A117948107/AONE?u=txshracd2488&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=af9dd3fa.

MATTHEW TURNER | Anti-Religion in Soviet Russia: Jehovah’s Witnesses or Capitalist Subversives?

Soviet anti-religion poster from 1984. View the full digital collections item at https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/soviet-poster/1064062

The Soviet “Dollar-sign Hook” propaganda poster released in 1984 seemingly depicts a Soviet man waving a set of papers while unwittingly being hooked from behind by a massive American dollar sign attached to an American lure. The man is green and sickly looking, and his screaming face and bulging eyes suggest he has gone mad. There is much to unpack in this poster, and it could undoubtedly be interpreted from multiple angles. One interpretation that deserves considerable attention, however, suggests that the man is or has been converted by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who were the targets of significant Soviet persecution in the 1970s and 1980s. The poster implies that the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ true aims are not religious, but political, and their strings are being pulled by capitalist overlords in America.

The Witnesses’ religion was fundamentally at odds with Soviet government and society. The 1960 Watchtower Witness publication, meant to be circulated to Witnesses around the world, noted that persecution in the USSR was due to the Witnesses’ “godly stand” on issues such as “regimentated service to the totalitarian state or compulsory worship of its images.” [1] Put simply, the Witnesses placed their devotion to God above their devotion to the Soviet State, and this was unacceptable to the Communist Party.

According to Emily B. Baran’s book, Dissent on the Margins: How Soviet Jehovah’s Witnesses Defied Communism and Lived to Preach About It, Soviet anti-Witness propaganda frequently depicted Witnesses as agents of Western, particularly American, political goals and subversion. [2] Baran writes: “Soviet accounts argued that for Witnesses, religion served solely as a ‘mask’ to hide their true political goals.” [3] She also asserts that the Soviets portrayed Witnesses and their converts as being duped by power-hungry Western leaders who capitalized on gullibility and hardship to spread harmful ideology. [4] This same idea can be seen in the text displayed on the “Dollar-sign Hook” poster, as it argues that “religious extremism” is deceiving gullible citizens into believing “slander against the Soviet Union,” the text written on the newspaper that the man is waving in the air as he preaches. It clearly attacks the Witnesses as political agents, tying them to infectious, depraved American ideas and Western capitalism. The man on the poster is unkempt and spewing disgusting filth out of his mouth, presumably representing the degrading effects of religious extremism and Western ideas on Soviet citizens.

A main contributor to suspicion was the headquarters of the Witnesses, which was based in Brooklyn, New York. New York represented the center of evil Western capitalism in the eyes of the Soviets, and the Soviets consistently accused Witnesses of espionage in an attempt to prove the religion’s true loyalty to the United States, claiming that Witnesses worked with American intelligence to gather information about the Soviet economy. [5] Baran demonstrates that “According to Soviet accounts, the reactionary capitalist West used the Witnesses as a tool to undermine Soviet attempts to build world peace and achieve communism.” [6] This can be seen in the “Dollar-Sign Hook” poster, as the massive capitalist hook of American economic ideas has ensnared the man in the poster espousing “religious extremism,” which was a common way of describing the Jehovah’s Witnesses in the Soviet Union.

While the man looks Soviet, he is really being controlled by the American lure at the top of the poster. The lure itself conveys the Soviet view that the hook has no bait on it. The dollar itself is meaningless and only a snare. American ideas may look like an enticing lure with substantive reward, but ultimately what awaits at the end of the line is a sharp hook.

[1] Watchtower. New York: Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania, 1960. 500. [2] Baran, Emily B. Dissent on the Margins: How Soviet Jehovah’s Witnesses Defied Communism and Lived to Preach about It. Oxford University Press, 2016, 147. [3] Baran, Dissent, 147. [4] Baran, Dissent, 145. [5] Baran, Dissent, 148. [6] Baran, Dissent, 148.

ANNA WILLIAMS | Free ≠ Good

Soviet anti-American poster from 1950. See the full digital collections item at https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/svoboda-po-amerikanski/1064161

This 1950 poster depicts the Soviet view of “freedoms” granted to Americans. In the background are New York City’s skyscrapers, with Wall Street labelled. The foreground features the Statue of Liberty with her lips sealed by a padlock representing money and a policeman ready to strike with his baton, handcuffs also at the ready. This depiction highlights the negative attributes that the Soviets saw in American life – greed and the powerful taking advantage of the weak. Surrounding Lady Liberty are four smaller pictures. Starting from the top right, there is an illustration of Ku Klux Klan members who have just hung a Black man, with the label “freedom of the individuals”. On the bottom right, there are people protesting in support of peace while a car labeled with a money sign holds policemen pointing their guns at the protesters with the label “freedom of association and meetings”. On the bottom left is a man looking through money glasses at a paper that reads “sentenced for holding communist views” with the label “freedom of opinion”. Finally, in the top left, there is a man with “Hearst Press” on his hat sitting on a bag of money using a rolled-up newspaper as a megaphone. Birds labeled with the swastika and the words “slander” “lies” and “provocation” are flying out of the improvised megaphone, and the panel is labeled “freedom of the press”.

The Hearst Press, at its peak in 1935, was the world’s largest publishing empire in terms of the number of newspapers and their combined circulations. [1] The publication, however, was known for supporting isolationist and nationalistic policies during a period in history that demanded American cooperation in international security efforts. [2] Hearst papers were notorious for publishing articles that supported William Randolph Hearst’s private beliefs, frequently leading to the distortion of news. [3] Starting in the mid-1930s, the Hearst Press began an intense anti-Communist campaign that included attacks on American educators and the Roosevelt administration. [4] Hearst openly applauded red-baiters in Congress, and an editorial proclaimed that every “patriotic and alert citizen in the United States” should “wear the badge of red baiting proudly”. [5] The Hearst papers endorsed early initiatives to outlaw Communism in the United States, and even proposed that Communism should not only be outlawed, but adherence to Communism should be considered high treason. [6] These radically anti-Communist views explain why the birds in the poster are labelled “slander”, “lies”, and “provocation” as the Hearst Press spread much of each as they attacked alleged Communists in the United States.

The Hearst papers endorsed early initiatives to outlaw Communism in the United States, and even proposed that Communism should not only be outlawed, but adherence to Communism should be considered high treason.

Hearst was also seen by some as being pro-German, especially early in his career, because in the summer of 1934, he visited Germany, interviewed Hitler, and entered into a news contract with the German government. [7] While his view on Germany and Hitler likely shifted during World War II, this visit made many suspicious of Hearst’s loyalties and explains the swastikas seen on the birds on the poster. Overall, the Hearst Press played a very important role in the anti-Communist sentiments in the United States in the mid-1930s to early 1940s. After World War II, the chaos and misinformation surrounding Communism before the war was certainly not forgotten, and the Soviet Union was able to point out that a free press did not necessarily equate to a good press.

[1] Edwin Emery, Highlights in the History of the American Press: A Book of Readings (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1954), 320. [2] Ibid., 324. [3] Ibid., 326. [4] Ian Mugridge, View from Xanadu: William Randolph Hearst and United States Foreign Policy (Montreal, CA: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1995), 79-87. [5] Ibid., 84. [6] Ibid., 84. [7] Ibid., 120.

HANNAH ZIMMERMAN | The False Promises of Democratic Freedom

Soviet anti-American poster from 1950. See the full digital collections item at https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/svoboda-po-amerikanski/1064161

At the height of the Cold War, both the U.S. and the USSR took advantage of opportunities to expose the weaknesses of their opponent. For the Soviets, the U.S. civil rights crisis was the perfect chance to highlight the evils of capitalism and democracy. Although the USSR had its own human rights issues, the Soviets were eager to point out the shortcomings of American freedom, and this is illustrated in the 1950 Soviet propaganda poster, Svoboda po-amerikanski (Freedom American-Style). [1] The poster’s main feature is the depiction of the Statue of Liberty surrounded by several disturbing images of civil liberty violations. The top-right corner of the poster illustrates “freedom of the individual,” and it shows the lynching of an African American. The Soviets used the civil rights struggle to argue that the quality of life in the USSR was significantly better and safer than it was in the U.S.

To prove that life in the Soviet Union was greater than in the U.S., the Soviets used the civil rights struggle to prove that not all Americans enjoyed equal freedoms. When considering this period of struggle between socialism and democracy, it is necessary to consider the irony of how the U.S. claimed to be a beacon of morality, while also discriminating against those within its own borders. [2] The Soviets manipulated civil rights to be an issue at the forefront of the Cold War narrative within their own country, and they hoped to convince the Soviet people – and a global audience in the era of decolonization – that there were no better options than a communist system. [3] The mistreatment of African Americans was a dilemma because the United States claimed to be the land of the free, but not all Americans enjoyed the fruits of democracy, and this made life in the USSR more appealing.

The forces of U.S. McCarthyism and paranoia about Soviet influence in the 1950s complicated the struggle for civil rights because those who fought for equality were often quickly accused of communism. [4] The case of Paul Robeson gained international attention and was mentioned several times in the Soviet press with the intent of highlighting the U.S.’s failure to keep their democratic promises of liberty. Robeson was an African-American musician, actor, and activist who was blacklisted in 1949 because he was critical of his country’s lack of equal civil liberties protection. Robeson, along with others like him, were silenced to preserve the “image of America, and [to] maintain control over the narrative of race and democracy.” [5] The censoring of his music and the attacks against him made Soviet news headlines, highlighting the dangers of life in America. In a series of 1949 Soviet news articles, the alarming and shocking headlines include titles such as “Outrages of American Fascists: Attempts to Lynch Paul Robeson,” “Persecution of Paul Robeson in the USA,” and “America’s Shame.” [6] The Soviets used Robeson’s situation to show their people that life in the U.S. was oppressive and even violent, and by exposing the evils of a capitalist nation, they hoped that people within the Soviet Union would appreciate their communist system all the more.

[1] B. Efimov, N. Dolgorukov, and A. Druzhkov, Svoboda po-amerikanski, Propaganda poster (Soviet Union, 1950). https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/svoboda-po-amerikanski/1064161 [2] Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 3 [3] Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights, 250. [4] Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights, 11. [5] Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights, 77. [6] “Outrages of American Fascists: Attempts to Lynch Paul Robeson,” “Persecution of Paul Robeson in the USA,” and “America’s Shame,” Current Digest of the Russian Press, 1949. https://dlib-eastview-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/search/pub/articles?pager.offset=0

Bibliography

Dudziak, Mary L. Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Efimov, B., Dolgorukov, N., and Druzhkov, A. Svoboda po-amerikanski. 1950, Soviet propaganda poster. Keston Center, Baylor University. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/svoboda-po-amerikanski/1064161

“Outrages of American Fascists: Attempts to Lynch Paul Robeson,” “Persecution of Paul Robeson in the USA,” and “America’s Shame,” Current Digest of the Russian Press, 1949. https://dlib-eastview-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/search/pub/articles?pager.offset=0