One hundred years ago, the Russian Revolution, actually a pair of revolutions which took place in February and October of 1917, shook the world. Food shortages, rapid currency inflation, and weariness with World War 1, among other things, led to an uprising in February which ousted Russian tsar Nicholas II and replaced his imperial rule with a provisional government. However, socialist-controlled local workers councils, called soviets, remained powerful because they enjoyed the loyalty of lower classes and much of the liberal middle class. Soviet leaders, the Bolsheviks, in particular, eventually capitalized on widespread disapproval of Russia’s continued involvement in WWI and led local militias to revolt in October. This revolution overthrew the provisional government and led to the formation of the Soviet Union and the rise of socialism, events which had lasting effects of such global magnitude that they changed history.

The revolution impacted every aspect of life in Russia, but especially religion. This exhibit highlights propaganda in the persecution of religion during the political and social upheaval following the 1917 Revolution, specifically how anti-religious rhetoric, suppression, and atheism reinforced, solidified, and extended Soviet rule. The exhibit tells the story of Saint Benjamin of Petrograd, analyzes various propaganda forms used by the Soviets, and shows images of destroyed churches that reveal the extent that the government feared and suppressed religion in post-revolution Russia.

In 1988, a professional photographer entered Russia to document the destruction of churches and create an exhibit of remembrance. The exhibit would have marked the Millennium of Christianity in Russia and could have served as a reminder of the persecution that the Church and people of faith endured. Unfortunately, the Soviets barred the photographer from Moscow, and the exhibit never occurred. Names, dates, and locations of the churches are unknown, a chilling testament to the efficiency of the Soviet repression. These photos are courtesy of Keston College, United Kingdom.

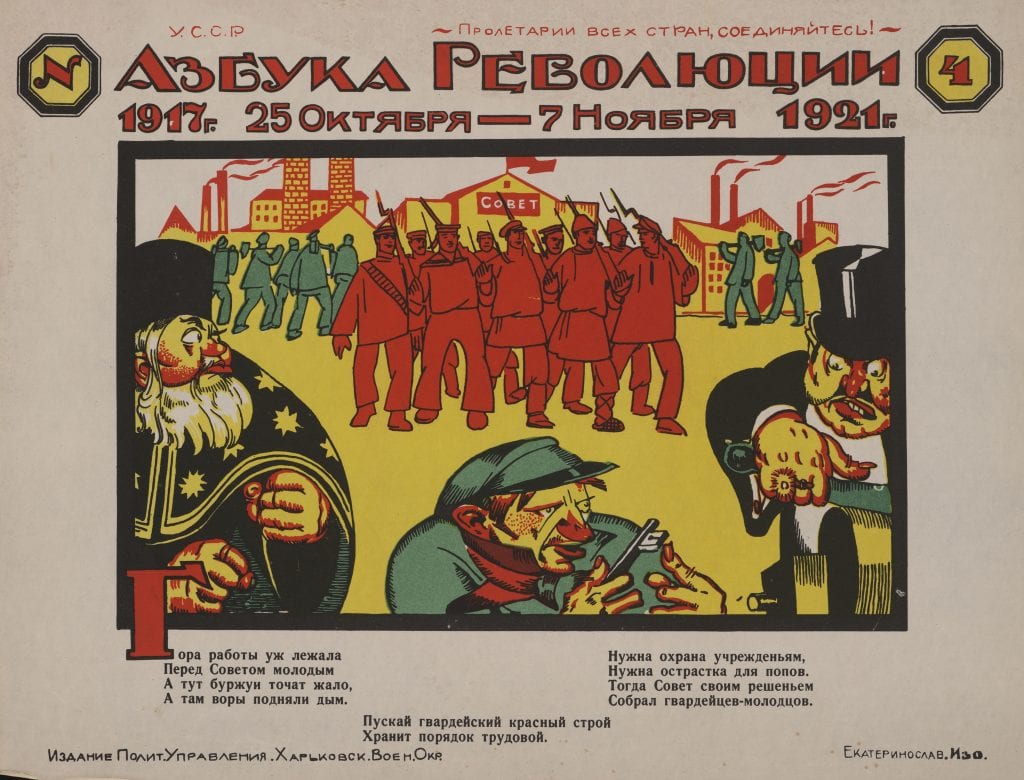

Propaganda furthers an agenda by influencing people to adopt ideas that alter their perception by presenting an emotionally charged narrative that prompts a calculated reaction which sways public opinion. Propaganda varies in form, including speeches, pictures, movies, music, and other media. Posters are particularly effective. The following political poster commemorates the Fourth Anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution in 1917 and was published by the Political Directorate of the Kharkov* Military District, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.**

The title: “Revolution from A to Z”

The poster shows a squad of Red Army guards armed with guns and ready to protect the order of work life. The four come from different backgrounds: sailors, soldiers, workers, and peasants and stand in front of an administrative building with a red flag on the top and the sign “Soviet” (Council). Factories with smoking chimneys and workers with hammers appear in the far background. The rhymed caption at the bottom can be summarized as follows: The “Soviet” needs guards to protect workers from forces which disturb the order. The three ominous figures in the foreground: a clergyman, a thief, and a bourgeois represent the forces. Each of them has an agenda and is ready for an action against the public authority. The clergyman will preach a religious ideology, the thief will steal public property, and the bourgeois will sponsor a counter-revolution. The two dates on the poster are October 25, 1917 and November 7, 1921,

The themes, imagery, and characters represented offer unique insights into post-revolution Russian life. Religion was feared because it promised an escape from the challenges of daily life through eternal salvation and answered to and worshiped a higher power. These themes did not fit the narrative that the Soviets were trying to create. The clergy was also viewed on the same level as the bourgeois in terms of ability to sway the populace and the danger they posed.

* In 1921 Kharkov (Khar’kov) was the capital city of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The capital was moved to Kiev in 1934.

** Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was established in 1919.

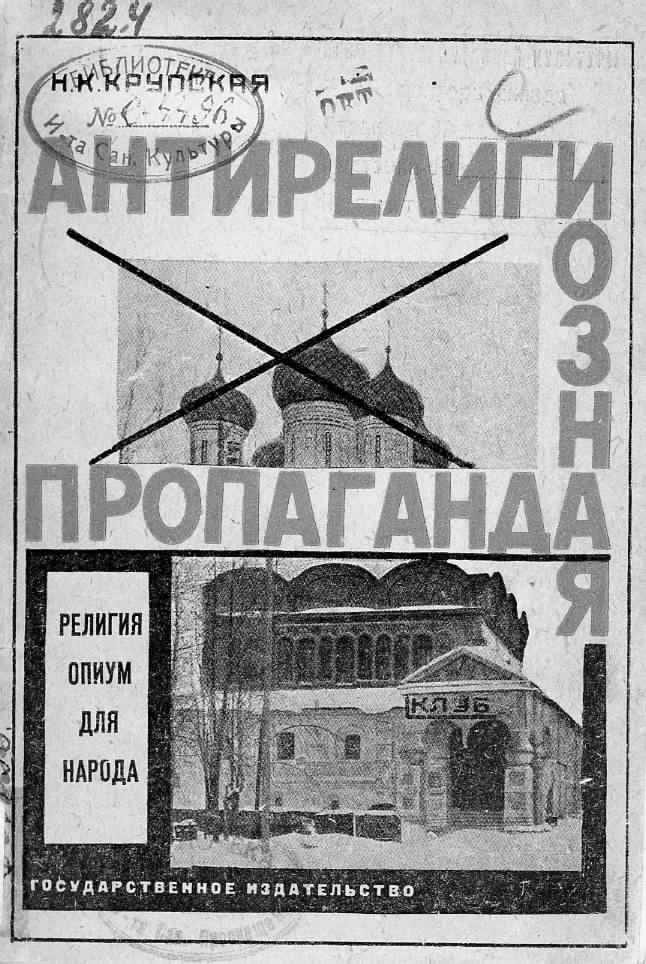

Antireligioznaia Propaganda (Antireligious Propaganda) by Nadezhda Krupskaia. Moscow: State Publishing House, 1929

Antireligioznaia Propaganda by Vladimir Lenin’s wife Nadezhda Krupskaia contains her articles in Communist newspapers and journals between 1922 and 1929. They discuss the goals of antireligious propaganda in Soviet schools and work places as well as the role of the arts in the antireligious and atheistic upbringing of children and youth.

The cover features a paraphrased statement of “Religion is the opium of the people” from German philosopher and economist Karl Marx’s work, A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right.

Ocherednye Zadachi Antireligioznoi Propagandy (The Immediate Tasks of Antireligious Propaganda) by Emel’ian Iaroslavskii. Moscow: Bezbozhnik, 1930.

The work contains the address and closing remarks of Emel’ian Laroslavskii at the Second Plenary Session of the Central Committee of the League of Militant Godless. Laroslavskii founded the League of Militant Godless.

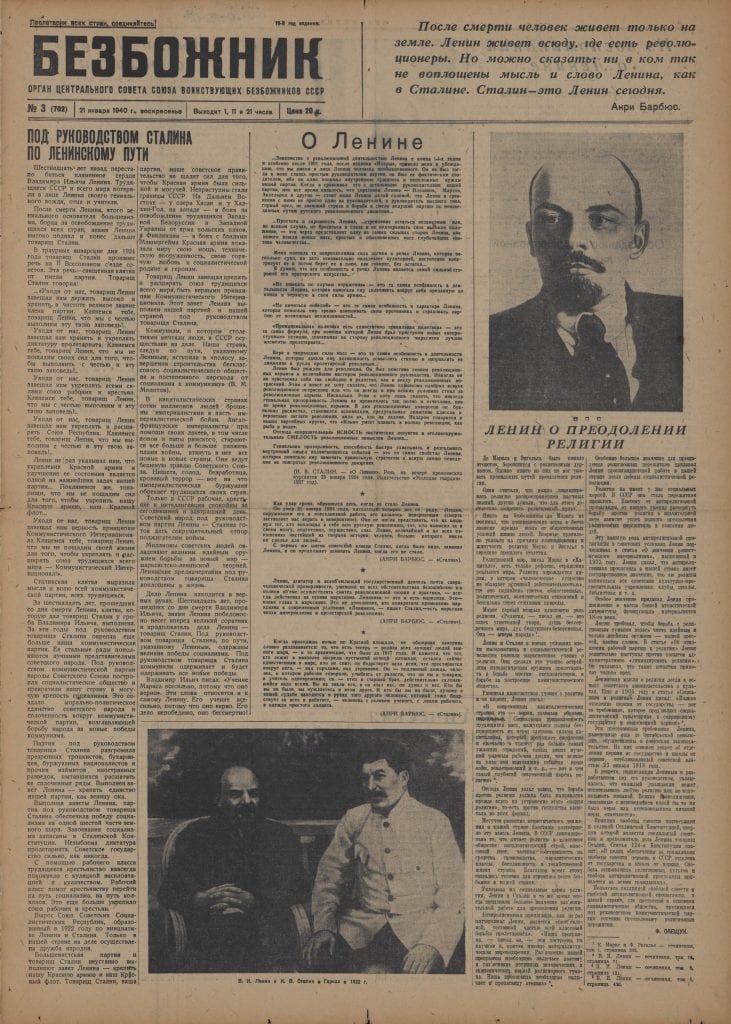

Bezbozhnik (Godless), No 3 (702) (21 January 1940)

The Central Committee of the League of Militant Godless of the USSR published the newspaper Bezbozhnik between 1922 and 1941. The January 21, 1940, issue is dedicated to the 16th anniversary of Vladimir Lenin’s death. The Henri Barbusse quote from Stalin (1935) on the front page reads in translation: “After the death, a person is alive only on Earth. Lenin is alive everywhere where there are revolutionaries. One may also say that it is in Stalin more than anyone else that the thoughts and words of Lenin are to be found. He is the Lenin of today.”

The issue also commemorates the 35th Anniversary of “Bloody Sunday” which marked the beginning of the 1905 Revolution in Russia.

St. Benjamin of Petrograd, an important bishop in the Russian Orthodox Church in the early 1900s, was born Vasily Pavlovich Kazansky and was raised in the northwest of the Russian empire. He graduated from seminary in 1893 and earned his theology degree from St. Petersburg Spiritual Academy in 1897. He spent the first thirteen years of his career in education, holding faculty positions in several seminaries and spiritual academies. He was tonsured a monk in 1895 and received the name Benjamin. In 1910, he became bishop of Gdov and spent the next seven years devoted to pastoral care and charity work. Benjamin became Metropolitan of Petrograd in 1917 (formerly St. Petersburg), a position he would hold until his death.

The year 1917 and those that followed were a tumultuous period in Russia because of the revolution and the rise of the Soviets. The Russian Orthodox Church attempted to maintain a neutral stance during the social and political upheaval even though Soviet authorities viewed the Church as dangerous and counter-revolutionary, “the opium of the people,” according to Karl Marx. In 1922 the Soviets demanded that churches hand over their valuables to aid in famine relief efforts. Benjamin agreed that the churches should help with famine relief but objected to the forced removal of sacred artifacts when church members were willing to substitute their own items of equal value. In return, Benjamin and several fellow priests were arrested and tried for counter-revolutionary activities. After a lengthy trial, they were found guilty and sentenced to death. Tragically, Benjamin and other leaders were executed by firing squad during the night of August 12-13, 1922 on the outskirts of Petrograd. Authorities had them shaved and dressed in rags so that the firing squad would not know they were killing clergy. Their remains were never found.

The Russian Orthodox Church canonized Benjamin in 1992, along with several of the other martyrs who died alongside him. He became known as St. Benjamin of Petrograd, and the celebration of his feast in the Russian Orthodox tradition is July 31.

- Veniamin Trial transcript 01

- Veniamin Trial transcript 02

- Veniamin Trial transcript 03

Case of Metropolitan of Petrograd and Gdov Veniamin (Vasilii Kazanskii)

The Court Summary and the Sentence

Having examined in a court session the materials of the preliminary investigation, the explanations of the representatives of prosecution and defense, and the testimonies of the witnesses and the accused themselves,

the TRIBUNAL has ESTABLISHED:

Kazanskii, also known as Metropolitan of Petrograd and Gdov, together with the Local Parish Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, represented by its active group: Head of Administration Novitskii and members Kovsharov, Elachich, Chukov, Bogoiavlenskii, Ognev, Shein, Plotnikov, Chil’tsov, Bychkov, and Petrovskii in the context of the counter-revolutionary directives issued by Patriarch Tikhon against the existence of the power of Workers and Peasants, aimed at carrying out the directives, disseminating ideas against the Soviet Authorities’ decree of February 23, 1922 on confiscation of church valuables, and causing public disturbances with the purpose of uniting with the world bourgeoisie against the Soviet Power.

…

…

Based on the foregoing, the tribunal has SENTENCED:

Kaznskii, Novitskii, Kovsharov, Elachich, Chukov, Plotnikov, Bogoiavlenskii, Ognev, Shein, Chil’tsov Mikhail to execution by shooting and confiscation of their property.

Bychkov and Plotnikov to imprisonment for three years in high security prison.

…

Former Patriarch Tikhon to be put under a criminal investigation.

The Sentence will take effect in 48 hours during which the sentenced individuals have the right for an appeal.

Original with the proper signatures

Certified

Secretary of the Petrograd Province Revolutionary Tribunal /Davydov

Impressive and meaningful exhibit on a very difficult but quite timely topic.